Gate Ventures Research Insights: The Third Browser War – The Battle for the Gateway in the AI Agent Era

TL;DR

The third browser war is unfolding beneath the surface. Historically, the battle for browser dominance—from Netscape and Microsoft’s IE in the 1990s, through the open-source drive of Firefox and the rise of Google Chrome—has been a reflection of platform control and shifting technological paradigms. Chrome secured supremacy with rapid updates and ecosystem integration, allowing Google to build a “dual oligopoly” between search and browser, creating a closed loop to information access.

Now, this landscape is under threat. Large language models (LLMs) are prompting a rise in “zero-click” search behavior, with users completing tasks directly in the results page and bypassing traditional web navigation. Meanwhile, rumors about Apple replacing the default Safari search engine further imperil Alphabet’s (Google’s parent company) core profit base, stoking market unease over the future of search.

The browser’s role is being reimagined—not just as a web display tool, but as a container for data input, user actions, privacy, and identity. While AI agents are powerful, they still rely on browsers to manage complex page interactions, access local identity data, and control web elements within trusted boundaries and secure sandboxes. Browsers are shifting from human-facing interfaces to system-level platforms for AI agents.

This article examines the continued relevance of browsers, arguing that real disruption won’t come from another “better Chrome,” but from an entirely new interaction paradigm—moving from information display to task invocation. Tomorrow’s browsers will be designed for AI agents—not only to read, but to write and execute. Projects like Browser Use are working to semanticize page structures, turning visual web interfaces into structured text callable by LLMs, dramatically lowering interaction costs.

Industry leaders are already experimenting: Perplexity is launching the native Comet browser with AI-driven search; Brave merges privacy and local inference to enhance search and ad-blocking; crypto-native initiatives like Donut are opening new pathways for AI and blockchain asset interaction. What these projects share is a focus on redefining browser input, rather than merely optimizing output.

For entrepreneurs, opportunity lies at the intersection of input, structure, and agent. As browsers become the gateway for agent-driven digital interaction, those providing structured, callable, and trusted capability modules will shape the next platform era. From SEO to Agent Engine Optimization (AEO), and from traffic analytics to task chain integration, product design and thinking are being reinvented. The third browser war is being fought over “input” rather than “display”—and its outcome will hinge not on who captures user attention, but who earns the agent’s trust and invocation rights.

A Brief History of Browser Development

In the early 1990s, before the Internet became a part of daily life, Netscape Navigator debuted like a ship discovering new worlds, opening the digital universe to millions. Not the first browser, but the first to truly reach the masses and shape the online experience, Netscape introduced easy graphical web browsing—making the world suddenly feel accessible.

But glory fades quickly. Microsoft soon saw browsers’ strategic value and bundled Internet Explorer with Windows, making it the default. This “platform killer” move shattered Netscape’s market lead, with users passively accepting IE due to system defaults. Powered by Windows, IE became ubiquitous, while Netscape entered decline.

Firefox Logo Evolution

Faced with adversity, Netscape’s engineers made a bold and idealistic choice—releasing the browser’s source code to the open-source community. Like a “Macedonian abdication” in tech, it signaled the end of one era and the rise of another. The foundation code led to the Mozilla browser project, initially Phoenix, finally renamed Firefox after several trademark hurdles.

Firefox was no mere Netscape replica—it delivered breakthroughs in user experience, plugin ecosystems, and security. Its launch was a landmark for open-source and revitalized the industry. Firefox was hailed as Netscape’s “spiritual successor”—a metaphor as resonant as the Ottomans inheriting Byzantium’s twilight.

Yet Microsoft had already released six IE versions before Firefox’s debut, and its time advantage and bundling left Firefox perpetually catching up. The race was never fair.

Elsewhere, Norway’s Opera browser emerged in 1994 as an experimental project. With its self-developed Presto engine from version 7.0 in 2003, Opera pioneered CSS support, adaptive layouts, voice control, and Unicode. Though its user base stayed small, Opera was a technical trailblazer and a “geek favorite.”

2003 also saw Apple launch Safari—a pivotal moment. Facing bankruptcy, Apple received a $150 million lifeline from Microsoft to preserve competitive optics and dodge antitrust scrutiny. While Safari’s default was Google Search, its complex history with Microsoft exemplifies the competitive–cooperative dance among Internet giants.

IE7 arrived with Windows Vista in 2007 to lukewarm reception, while Firefox gained ground with faster updates, open extensions, and developer appeal—raising its market share to roughly 20%. IE’s dominance wavered as Firefox surged.

Google pursued a different strategy, incubating its browser project from 2001 and persuading CEO Eric Schmidt to approve it after six years. Chrome launched in 2008, built on Chromium and WebKit, and—though disparaged as “bloated”—leveraged Google’s expertise in advertising and branding to ascend rapidly.

Chrome’s edge was in frequent updates (every six weeks) and a unified cross-platform experience. In November 2011, Chrome overtook Firefox with 27% market share; within six months, it surpassed IE, completing its rise to market leader.

Meanwhile, China’s mobile internet fostered its own ecosystem. Alibaba’s UC Browser soared in early 2010s, especially in India, Indonesia, and China, favored by low-end device users for its lightweight design and data-saving features. In 2015, UC captured 17% global mobile share—46% in India alone. But intensified Indian scrutiny of Chinese apps soon pushed UC out of key markets, ending its run.

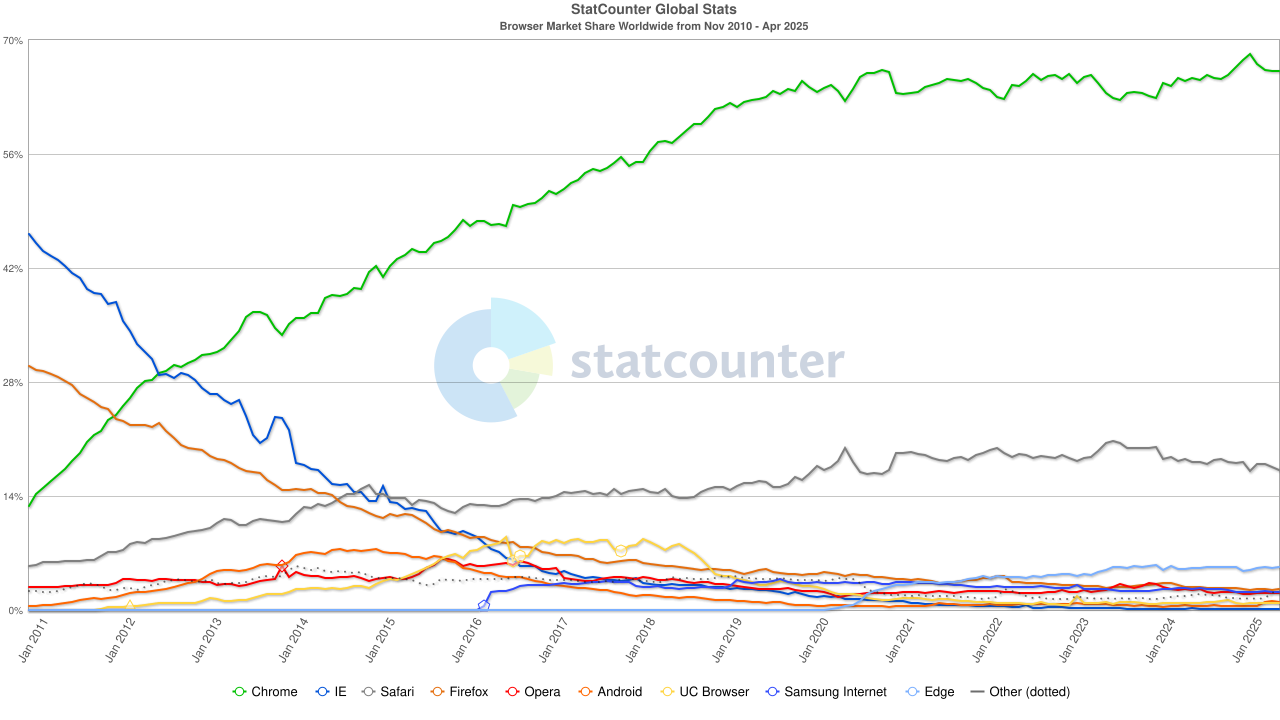

Browser market share, source: statcounter

By the 2020s, Chrome had locked down about 65% of the global browser market. Google Search and Chrome may both fall under Alphabet, but they dominate separately—Search controls about 90% of global queries, while Chrome is the main gateway for most users.

Protecting this dual monopoly, Google invested heavily—paying Apple roughly $20 billion in 2022 to remain Safari’s default search. Analysts estimate this cost is 36% of Google’s Safari-derived ad revenue—a “protection fee” for its business moat.

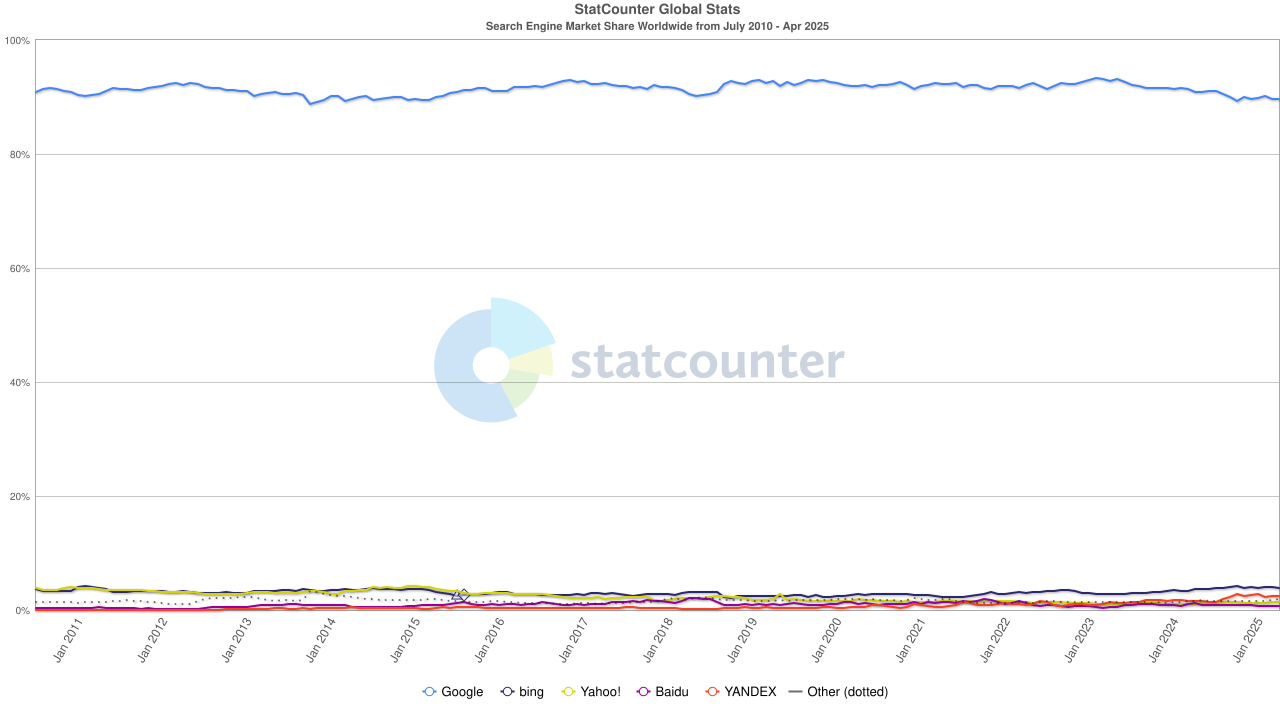

Search Engine market share, source: statcounter

Now, the winds are shifting again. LLMs are eroding traditional search; in 2024, Google’s share dropped from 93% to 89%. More disruptive are rumors of Apple launching its own AI search—if Safari defaults to an Apple model, Alphabet’s profit and market structure may be upended. Investors responded instantly, with Alphabet stock dropping from $170 to $140—reflecting market anxiety about search’s future.

From Navigator to Chrome, open-source dreams to ad-driven business, lightweight browsing to AI assistants—the browser wars have always been about technology, platform, content, and control. The battlefield shifts, but the essential question remains: whoever owns the entry point shapes the future.

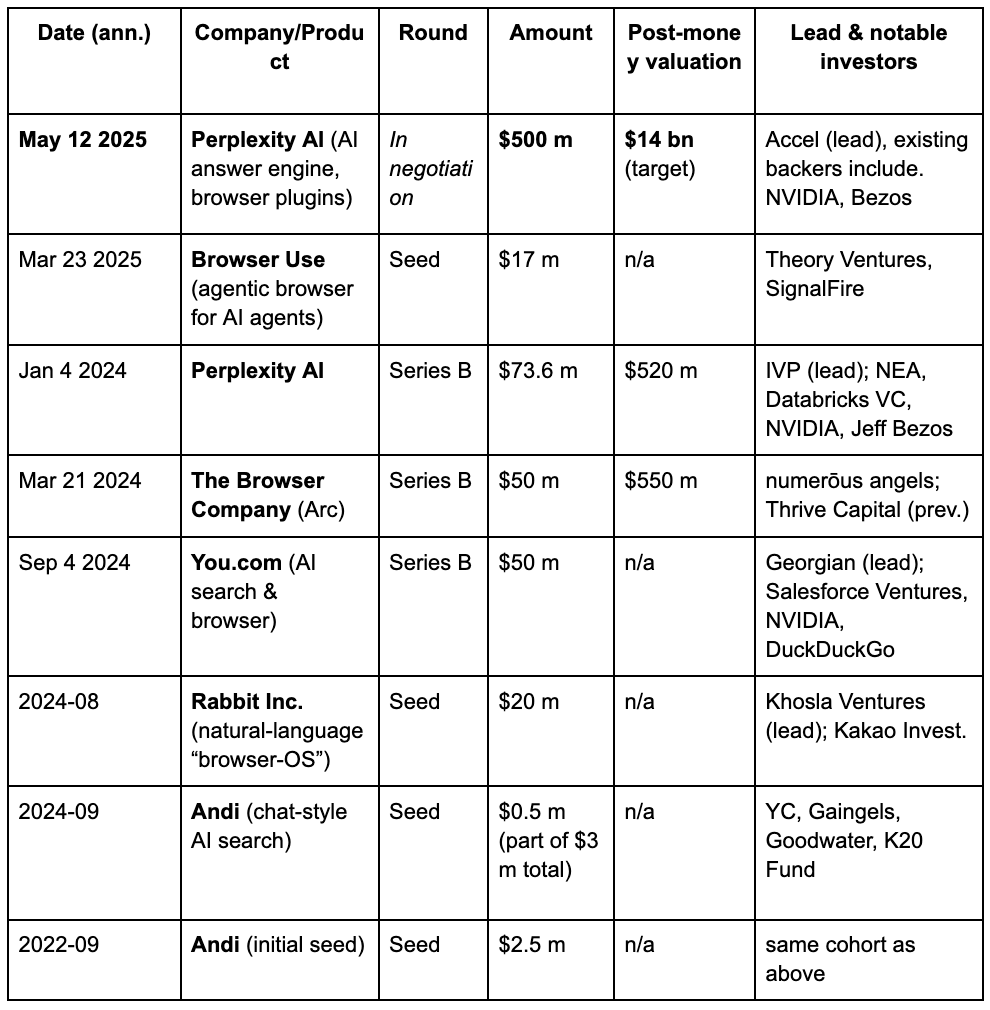

Venture capital sees the third browser war emerging, driven by AI-powered shifts in search demand. The chart below highlights recent funding rounds for leading AI browser projects.

Gate Ventures

Outdated Architecture of Modern Browsers

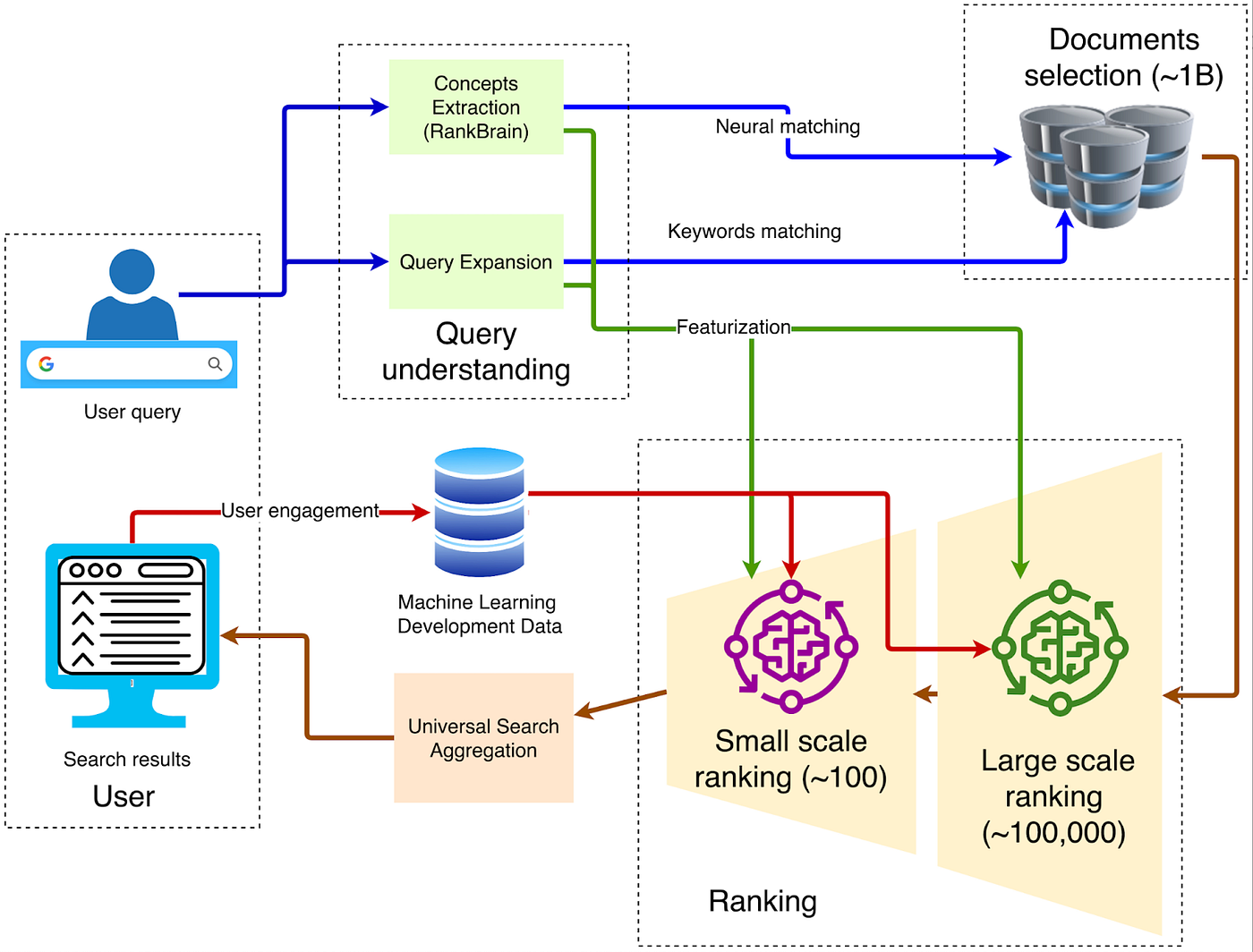

Classic browser architecture is illustrated below:

The overall architecture, source: Damien Benveniste

1. Client—Frontend Entry

User queries go over HTTPS to the nearest Google Front End for TLS decryption, QoS sampling, and geo-routing. Abnormal traffic (DDoS, automated scraping) can be throttled or challenged here.

2. Query Understanding

Frontend interprets user input in three steps: neural spell correction (“recpie” → “recipe”), synonym expansion (“how to fix bike” → “repair bicycle”), and intent parsing to classify queries and route vertical requests.

3. Candidate Recall

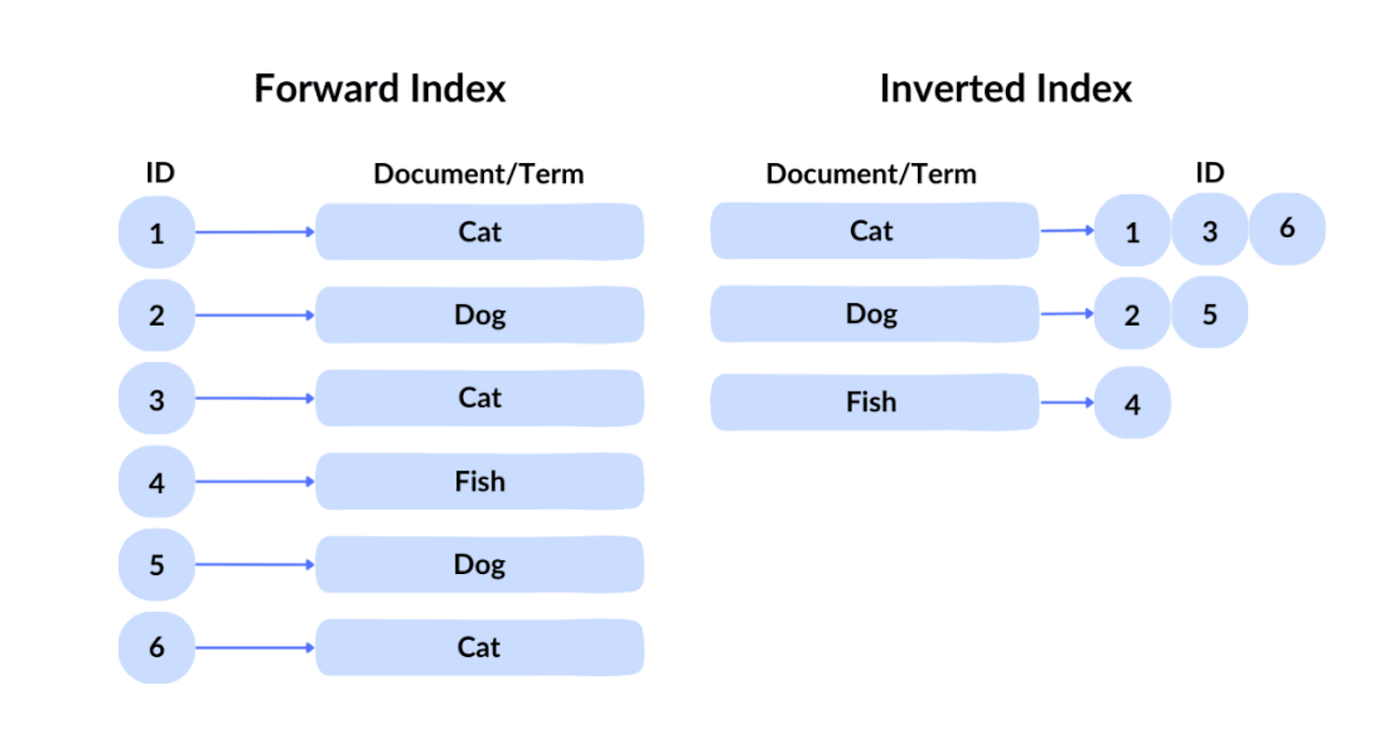

Inverted Index, source:spot intelligence

Google uses inverted indexing for queries. Unlike forward indexes keyed by file ID (which users can’t know), inverted indexes locate files via keywords. Google then applies vector indexing for semantic search, converting texts and images into high-dimensional embeddings and searching by similarity. For example, “how to make pizza dough” can return “pizza dough making guides.” Typically, about 100,000 pages make the initial cut.

4. Multi-Tier Ranking

Features such as BM25, TF-IDF, page quality scores, and thousands of data dimensions winnow 100,000 candidates to around 1,000, forming the preliminary set—this is the realm of recommendation engines. Features derive from user behavior, page attributes, query intent, context, time, day, and real-time news.

5. Deep Learning for Primary Ranking

Google’s RankBrain and Neural Matching interpret query semantics and select relevant documents. RankBrain (since 2015) converts queries and docs into vectors for semantic matching, aiding even novel queries. For example, “how to make pizza dough” matches “pizza basics.” Neural Matching (since 2018) uses neural nets to match queries and documents even when wording diverges, e.g., “laptop fan is loud” may match guides on overheating, dust, or CPU usage.

6. Deep Re-Ranking: BERT Model

After initial filtering, Google applies BERT to refine results, prioritizing relevance. BERT jointly encodes queries and docs to compute relevancy—e.g., “parking on a slope without curb” cues BERT to return advice for roadside wheel positioning. For SEO professionals, mastering Google’s ranking and recommendation algorithms is essential to optimize for top placement.

That’s the typical Google search workflow. But in the age of AI and big data, browser interactions are evolving.

Why AI Is Remaking Browsers

Why do browsers persist—could there be a third paradigm beyond AI agents and browsers?

In short, they’re irreplaceable. AI can use browsers but cannot replace them because browsers are universal platforms for both reading and inputting data. The digital world is not just about accessing information, but generating data and interacting. Browsers integrating personalized user data remain essential.

Browsers are more than just reading gateways; users also need to interact with data. They offer ideal storage for user fingerprints and privacy tokens. Advanced user and automated actions require browser mediation for secure, trustless calls. The data interaction sequence evolves to:

User → AI Agent → Browser.

The replaceable part is where the world trends—toward intelligence, personalization, and automation. AI Agents can handle some functions, but are unsuited for storing personalized content due to security and usability limitations:

Browsers are uniquely suited for personalized content storage because:

- Most LLMs are cloud-hosted; session info is server-side, making direct calls to local credentials, wallets, or cookies difficult.

- Transmitting all browsing or payment data to a third-party model requires reauthorization, and EU DMA/US privacy laws demand data minimization and localization.

- Actions like filling 2FA codes, camera use, or GPU inference must occur in-browser sandboxes.

- Data context—tabs, cookies, IndexedDB, caches, passkeys, extension data—resides in browsers.

Profound Paradigm Shifts in Interaction

Browser use splits into data reading, input, and interaction. LLMs have transformed how efficiently and intuitively we read data—keyword search now feels slow and old-fashioned.

Studies show user behavior is shifting—toward “summary answers” and away from page clicks.

Recent research (2024) found that in the U.S., just 374 of every 1,000 Google queries result in a click-through; 63% are “zero-click,” with users directly accessing weather, exchange rates, or information cards.

Psychologically, a 2023 survey showed 44% of users trust standard organic results more than featured snippets; academic studies reveal that for contested topics, users prefer results listing multiple source links.

Some users mistrust AI summaries, but many have adopted “zero-click” habits. Thus, AI browsers must balance interaction types for reading data; as LLM “hallucinations” remain, users remain cautious with auto-generated summaries. Improvement here is evolutionary, not disruptive.

The real ground for browser transformation is interaction. Historically, users interacted via keyword input—the browser’s interpretive limit. Now, users describe complex tasks in natural language, e.g.:

- “Find direct flights between New York and Los Angeles for a given period”

- “Find a flight from New York to Shanghai, then to Los Angeles”

For humans, these tasks demand multi-site data gathering and cross-checking; Agentic Tasks are increasingly handled by AI agents.

This aligns with historical trends—automation and intelligence. Workflows are shifting to AI Agents embedded in browsers. Future browsers must support fully automated processes, attending to:

- Human readability versus agent parse-ability

- Serving both users and AI agents within a single page

Only by meeting both can browsers serve as agent task platforms.

We now highlight five key projects: Browser Use, Arc (The Browser Company), Perplexity, Brave, and Donut. Each points to future directions for AI browsers and native Web3/Crypto integration.

Browser Use

This is why Perplexity and Browser Use have attracted significant funding. Browser Use stands out as a top innovation opportunity in 2025.

Browser Use, source: Browser Use

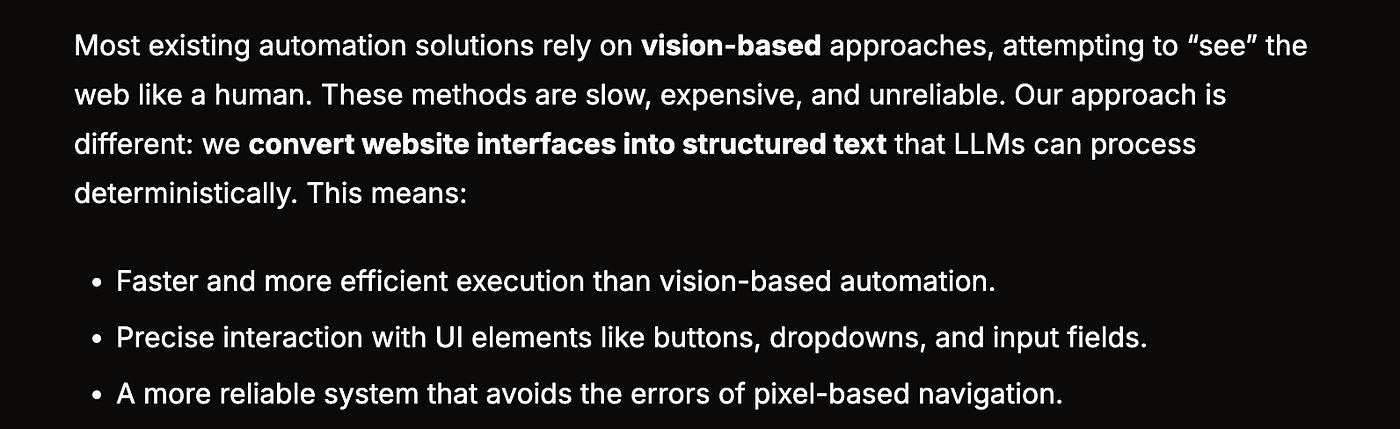

Browser is building a semantic layer for next-gen browser interaction.

Browser Use reinterprets the DOM not as a visual tree for humans but as a semantic command tree for LLMs—enabling agents to click, fill, or upload precisely without scanning visual coordinates. Structured text and function calls replace visual OCR or coordinate-driven Selenium, resulting in faster, more efficient execution. TechCrunch dubbed it “the glue layer that lets AI actually read the web”; the $17 million seed round in March bet on this foundational breakthrough.

After HTML renders the DOM tree, the browser builds an accessibility tree for screen readers, enriching elements with roles and states.

- Interactive elements (

- The page is mapped to a semantic node list for batch consumption by LLMs

- LLMs output high-level commands (e.g., click(node_id=”btn-Checkout”)), replayed in the browser. The official blog calls this “transforming site interfaces into LLM-parsable structured text.”

If adopted by W3C, this standard could solve input problems across browsers. The Browser Company’s open letters and cases further clarify where their approach diverges.

Arc

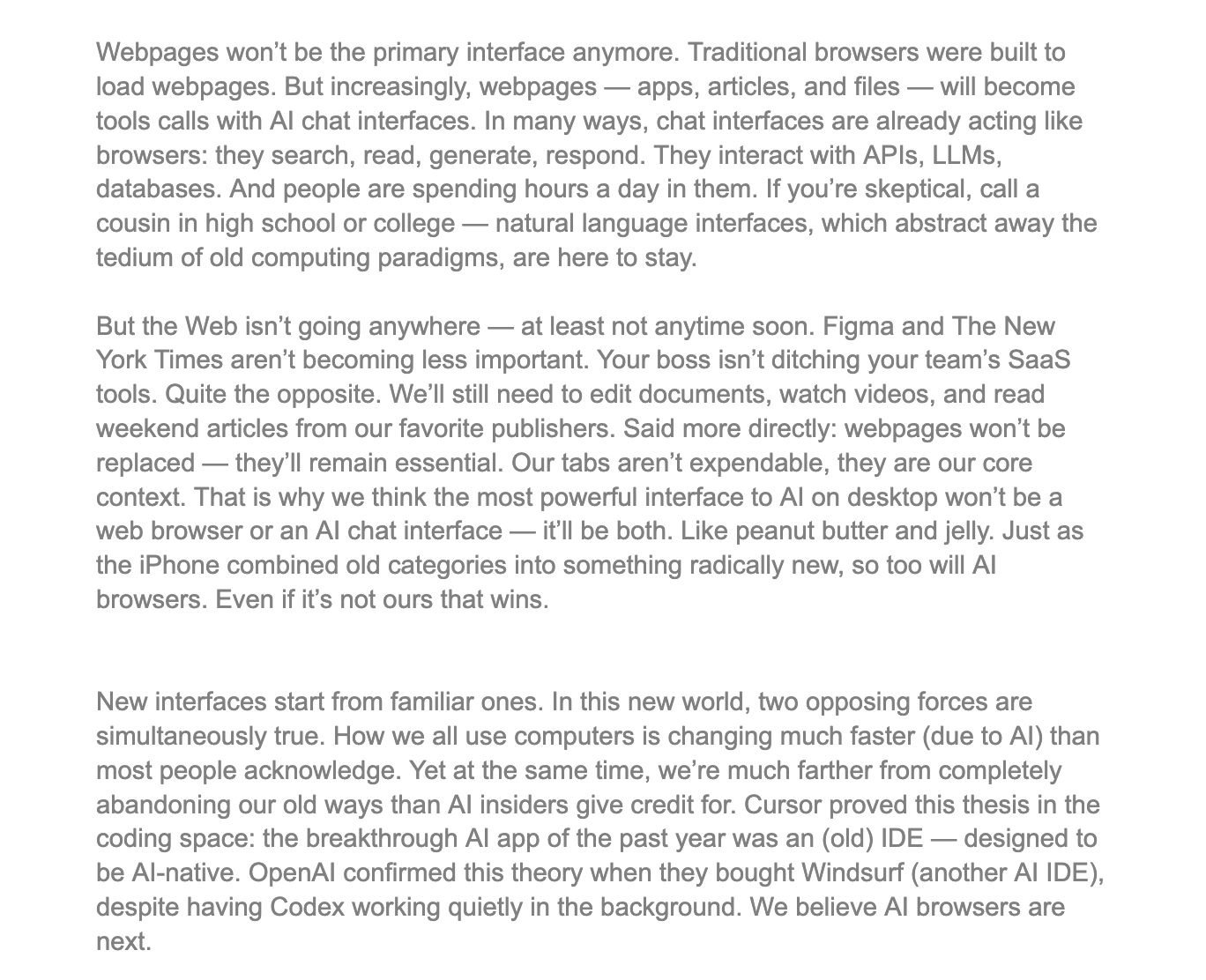

The Browser Company (Arc parent) announced ARC Browser will move to maintenance mode, with focus shifting to the AI-first DIA browser. Their open letter admits DIA’s future path is uncertain but makes several predictions about browser market trends. We believe only transformative output-side changes will disrupt the landscape.

Three predictions from ARC:

https://browsercompany.substack.com/p/letter-to-arc-members-2025

First, they suggest web pages will no longer be the core interaction interface—a tough claim that, in our view, undervalues browsers and overlooks a critical flaw in the AI browser vision.

LLMs are excellent at intent detection (“book me a flight”) but limited in supporting high-density information needs. When users require dashboards, Bloomberg Terminal-style notebooks, or visual canvases like Figma, pixel-precise web interfaces are unmatched. Custom ergonomics—charts, drag-and-drop, hotkeys—compress cognitive load, and are impossible in pure conversation-based interfaces. For Gate.com, investment actions need high input fidelity and structure, not just chat.

ARC’s vision falters by not distinguishing between input and output in interaction. While AI can streamline command inputs, the output side is lopsided, dismissing browsers’ vital role in presenting information and enabling personalized experiences. Reddit and AAVE exemplify distinct layouts and structures impossible to standardize. Browsers, as vessels for private data and diverse interface rendering, are hard to supplant, especially for output complexity. Most AI browsers today focus on “output summarization”—condensing page content, but this doesn’t threaten Google or mainstream search, only taking a slice of summary-driven traffic.

Thus, real disruption will not come from another Chrome, but from remaking browser rendering to suit agent-led interaction—especially through input architecture. Browser Use’s bottom-up restructuring is thus a more promising path, as atomic and modular systems yield programmatic and combinatorial power.

In short, AI Agents remain dependent on browsers, which will continue as the core data and app gateway. With deeper agent integration for fixed tasks and app interaction, browser models must evolve for agent compatibility and maximize use cases.

Perplexity

Perplexity, an AI search engine famed for its recommendation engine, is newly valued at $14 billion—nearly fivefold growth since June 2024. It handled over 400 million queries in September 2024, with an 8x increase year-on-year and 30 million monthly actives.

Its core is real-time page summarization, excelling at instant information. Earlier this year, Perplexity started building Comet—a browser meant to “think” about the web, not just display it. The answer engine is deeply embedded, echoing the Steve Jobs “whole-device” model, with AI tasks built into the core rather than as sidebar plugins. It’s designed to replace traditional search result links with concise cited answers, and directly challenge Chrome.

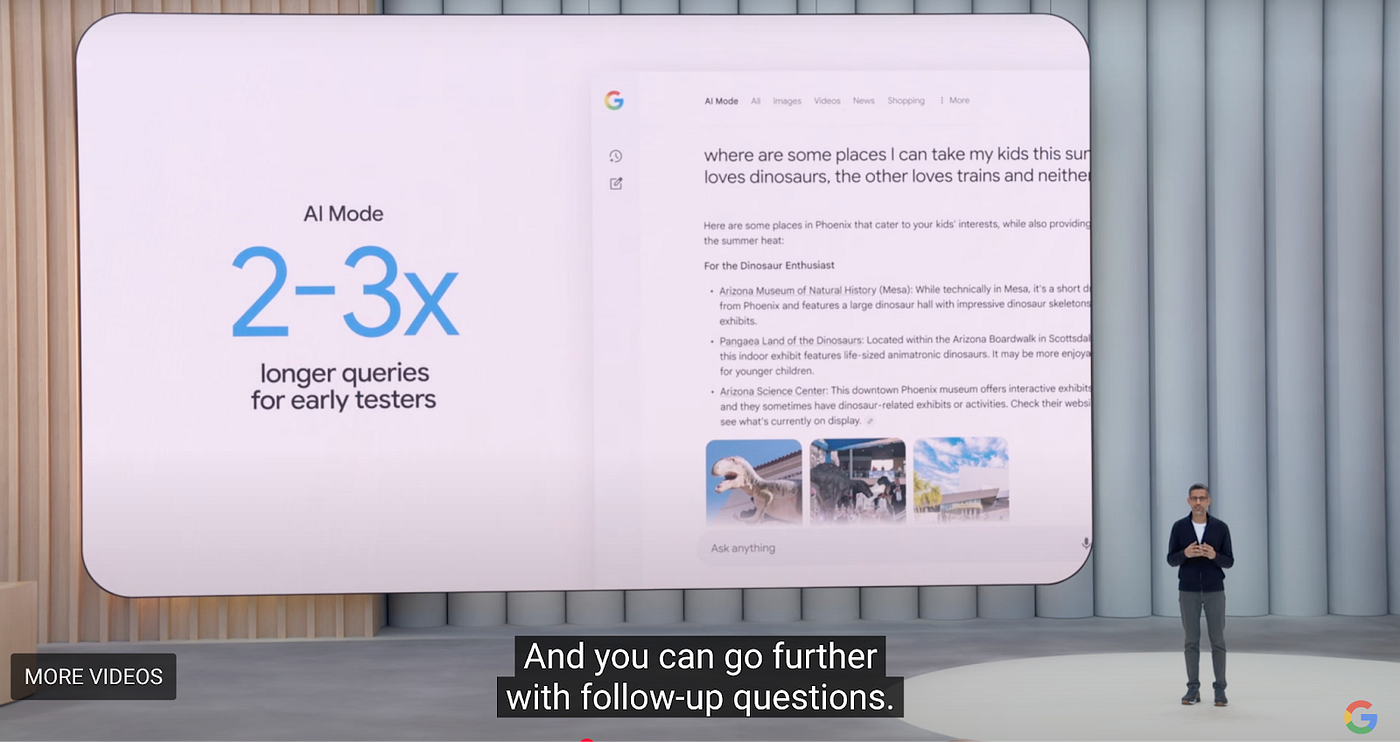

Google I/O 2025

Yet two obstacles remain: high search costs and low margins for marginal users. Even as an AI search leader, Google’s 2025 I/O announcements revealed ambitious AI upgrades, launching the “AI Model” browser tab experience, including Overview, Deep Research, and future agentic features (“Project Mariner”).

With Google aggressively pursuing AI, duplicating features (Overview, DeepResearch, Agentics) won’t suffice to topple the incumbent. True innovation will require rebuilding browser architecture from the ground up, embedding LLMs in the browser core, and reinventing interaction models.

Brave

Brave is a crypto browser pioneer, based on Chromium and compatible with Google Store plugins. Its privacy-first, browse-to-earn token model appeals to a niche segment, showing growth but unlikely to disrupt the mainstream.

Brave’s monthly active users hit 82.7 million, daily actives 35.6 million, holding about 1–1.5% of the market. Its growth is steady: from 6 million in July 2019, to 25 million in January 2021, 57 million in January 2023, and over 82 million by February 2025. Monthly search queries are 1.34 billion—just 0.3% of Google’s.

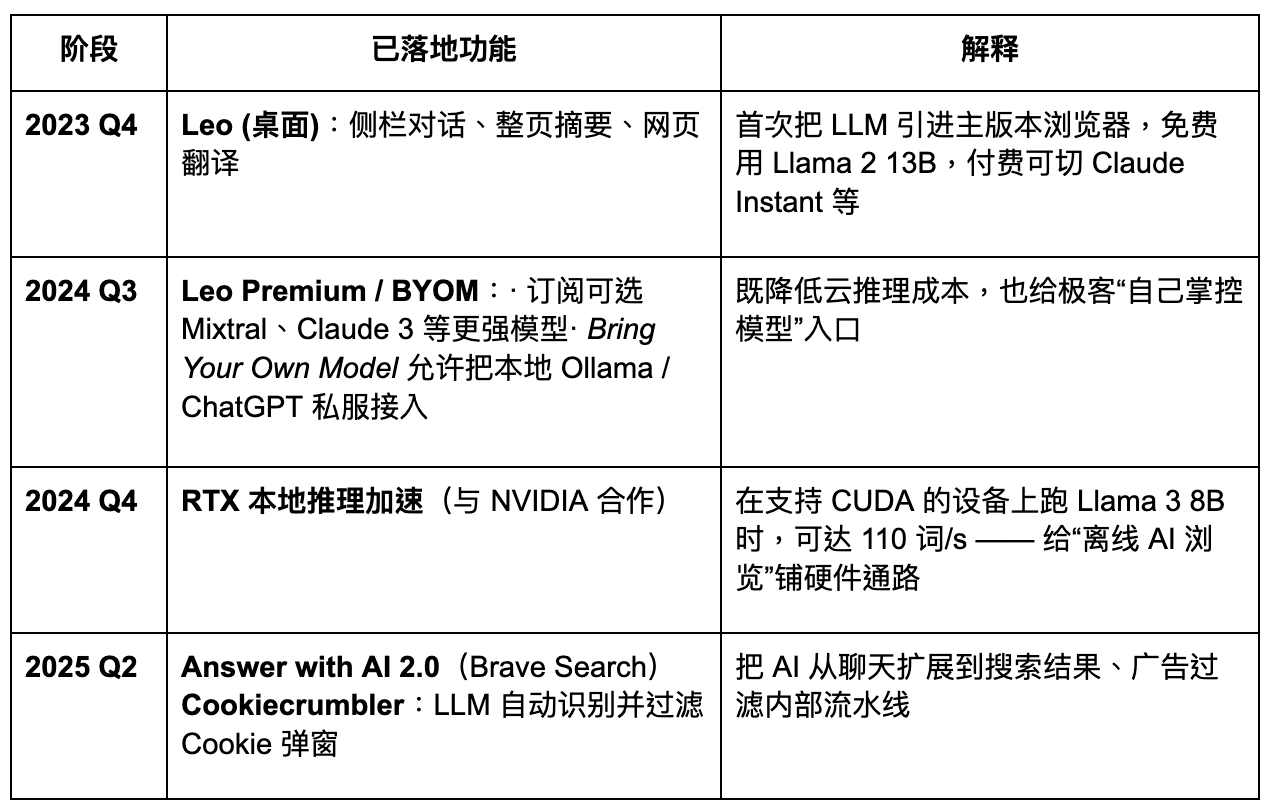

Brave’s roadmap below:

Gate Ventures

Brave is evolving into a privacy-first AI browser, but its limited user data hampers model customization and quick, precise feature releases. In the coming Agentic Browser era, Brave will hold a steady niche among privacy-focused users, but is unlikely to lead. Its AI assistant Leo is fundamentally a plugin for summarization, not a full agentic strategy; interaction innovation is still lacking.

Donut

The crypto industry is making moves in agentic browsers—Donut raised $7 million in pre-seed funding led by Hongshan (Sequoia China), HackVC, and Bitkraft Ventures. Still in early stages, Donut aims for unified Discovery, Decision-making, and Crypto-native Execution.

The core: automating crypto-native execution. As a16z predicts, agents may soon replace search engines for traffic, with startups competing for agent-initiated conversion, not Google search ranking. This trend is called Agent Engine Optimization (AEO) and Agentic Task Fulfilment (ATF)—not optimizing for ranking, but for being callable by agents to complete tasks like purchases, bookings, messaging.

Advice for Entrepreneurs

The browser remains the internet’s largest untouched “main entry”—with 2.1 billion desktop and over 4.3 billion mobile users worldwide as carriers for input, interaction, and fingerprint data. Browsers endure not by inertia, but because they are both “read” and “write” portals.

Real disruption doesn’t come from output-side tweaks. Even replicating Google’s AI summaries is plugin iteration, not paradigm shift. The true breakthrough is input-side: making your product callable by AI agents for task completion. This will decide if your product embeds in agentic ecosystems and captures new value.

Search was about “clicks”; the agent era is about “calls.”

As a founder, rethink your product as an API module—agents shouldn’t just “read” it, but “call” it. Product design should prioritize three dimensions:

1. Standardized Interfaces: Is Your Product Callable?

Agent callability hinges on structural standardization—abstracting information into schemas. Can critical actions (registration, orders, comments) be mapped via semantic DOM or JSON? Is there a state machine for agents to replicate user flows? Are interactions scriptable? Is there a stable WebHook or API?

This underpins Browser Use’s success—transforming HTML rendering into LLM-callable semantic trees. For founders, designing products with agentic structure is the key to future readiness.

2. Identity & Trust: Can You Bridge Agent Security?

Agents need a trusted intermediary for transactions and asset access—can you provide this? Browsers natively access local storage, wallets, codes, and 2FA, making them superior to cloud-only models. For Web3, lack of standardized asset interfaces means agents require local “identity” or “signing” capability.

This opens an imaginative frontier for crypto founders—a “Multi Capability Platform” for blockchain: general instruction layers for agent–Dapp calls, contract interface sets, or lightweight wallet/identity hubs.

3. Rethinking Traffic: From SEO to AEO/ATF

Where you used to pursue Google’s algorithm, now you must be embeddable in agentic task chains. Products must have clear task granularity—not just “pages,” but callable capability units—and support for agent optimization (AEO) or scheduling (ATF). Registration, pricing, inventory, and other flows should be structure-ready for agent calls.

Different LLMs have unique calling syntax (OpenAI vs. Claude). Chrome is the gateway to the old world; the future is connecting existing browsers to agentic workflows.

Your focus should be building “interface grammar” for agent calls, securing a link in the trust chain, and constructing the next “API fortress” for search.

If Web2 was UI-driven for user attention, the Web3 + AI Agent era is defined by call chains capturing agent intent.

Disclaimer:

This material does not constitute an offer, solicitation, or advice. Always seek independent professional guidance before making investment decisions. Gate and/or Gate Ventures may restrict or prohibit services in certain regions. Refer to the applicable user agreements for details.

About Gate Ventures

Gate Ventures is the venture capital arm of Gate, specializing in investments across decentralized infrastructure, ecosystems, and applications poised to reshape the world in the Web 3.0 era. Gate Ventures partners with industry leaders globally, empowering innovative teams and startups to redefine social and financial interactions.

Official Site: https://ventures.gate.com/

Twitter: https://x.com/gate_ventures

Medium: https://medium.com/gate_ventures

Related Articles

Gate Ventures Weekly Crypto Recap (September 29, 2025)

Gate Ventures Weekly Crypto Recap (October 6, 2025)

Gate Ventures Weekly Crypto Recap (September 22, 2025)

Gate Ventures Weekly Crypto Recap (October 20, 2025)

How On-Chain TCGs Could Unlock the Next $2 Billion Market: Landscape Overview and Valuation Outlook